If we better measure what we value, will we be better at valuing it in our collective life?

By Nancy Hey

This summer the UK Treasury published its guidance on Valuation of Wellbeing for use in policy making, business cases and evaluation. This guidance means that wellbeing science can be used robustly, consistently and with confidence at all stages of public policy. They have done this because the purpose of the Treasury’s appraisal process is to ensure that all significant costs and benefits that affect the welfare and wellbeing of the populations, not just market effects, are taken into account. For example, environmental, cultural, health, justice and security are included for the whole population that is served by the government, and not just tax payers.

This is an attempt to put some numbers, process and rigour on things that we value but are hidden in our economic national accounts. This has been called our ‘hidden wealth’; the value of unpaid care that we give, the love we have, the freedom we have to make choices, of our health and the trust we give to those around us, that keeps life worth living and the economy moving. This is important because GDP is silent on values. It’s a measure of activity that is good at helping us meet basic needs of populations, but that doesn’t care about how good our marriages are or our democracy is, how fair or sustainable our way of life is, whether we help each other out, keep people safe or have fun. But these are important to us as humans and this is what values are – things that are important to us.

The crisis of values

In his book, Values, Mark Carney, the former Governor of the Bank of England, argues that we have a common crisis of value and values. The Valuation of Wellbeing aims to tackle some of the latter by putting a value on things that are important to us as humans living together. He argues that with GDP the narrow focus of our vision, we have undervalued resilience, our social contract and what matters to our collective wellbeing; That GDP has both a rate of growth as well as a direction and quality. What is the purpose of all that GDP? Surely to improve lives. In the book he ends up describing the markets’ measurement of pain by the amount of opioids consumed and pleasure by the quantity of fizzy drinks sold which says a lot about how we’ve ended up with a dual crisis of health and misery as well as climate.

Our shared civic institutions and shared civil life are struggling in places too; this is the crisis of values. Rather than reinforcing our social and natural capital, we have consumed it and the quality of society, our trust in our public institutions that embody our shared way of life, is shaky. Our values are what’s important to us and are visible in the shared norms, everyday habits, shared understandings, expectations and behaviours we live everyday. This set of norms, our shared applied ethics of what’s ok and not are the principles and standards of behaviour we feel is right. We apply these values and ethics in our shared rules and laws that are increasingly creaking in our increasingly diverse, globalised and secular world. We would do well to revise our shared norms and practical ethics. Values, especially those that underpin our wellbeing, a missing link.

This is particularly important when we are in crisis and the problem is either novel, not a simple one or both. It is also increasingly the case when we speed up systems as we are doing with technology. These are examples of Fast Thinking and Fast Systems where we don’t have time to do full considered responses and act quickly and instinctively. It shows the state of our values. Trust in and resilience of our institutions is built when we respond well and have thought ahead, so we must make space to do this thinking and wire it into our systems to respond both fast and well.

Measuring meaning and purpose

One of the newer areas of wellbeing measurement, although not a new area of thinking about living good lives, is the concept of eudaimonia; sometimes called our sense of meaning and purpose, it describes the ideas that living well is not just about pleasure, but also about virtue and doing what is worth doing. There is a growing field of science and practice with advice on finding community, and having a working life or business filled with purpose; Arguably the best definition of community is as ‘a place with meaning’. Whether something has meaning or worth to us is very much about what we think is important, that it matters to us – it is what we value.

What matters for our sense of purpose?

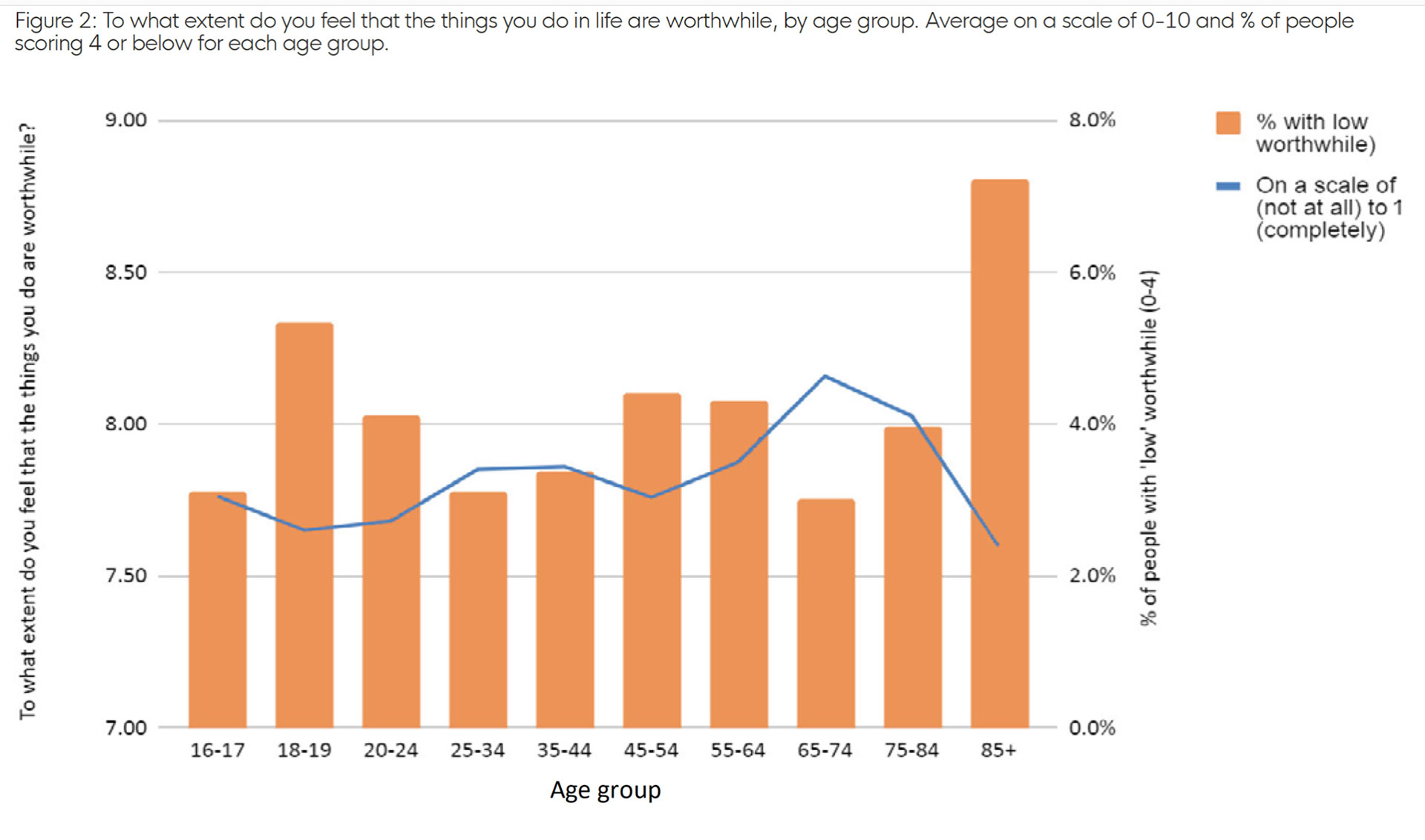

On a scale of 0-10 with 0 being not at all and 10 being completely, to what extent do you feel the things that you do in life are worthwhile?

For the last 10 years, as part of our national statistics, the UK has been measuring whether we feel what we do in life is worthwhile. This data is amazing and pioneering; it’s the first of its kind in the world. Our team at the What Works Centre for Wellbeing, together with our partners at Centre for Thriving Places, have done the first ever analysis of this data treasure trove. We hope what we find will make us all better able to understand ‘value’ in our systems of decision-making. This is what we found:

In the UK, people on average have a high sense that the things that they do are worthwhile. There are around 2 million people, or 3.8% of adults in the UK, who report a low sense of the worthwhile measure. From this, we can see that in the UK:

- Women have a higher sense of worthwhile than men.

- Married or cohabiting people have a higher sense of worthwhile than single people.

- People in their late 60s and early 70s have the highest sense of worthwhile and the smallest proportion of people with low worthwhile. This is consistent with where we see life satisfaction and happiness scores at their highest.

- People over the age of 85 had the lowest sense of worthwhile with more than 7% with low scores.

- Young people aged 18 to 24 also had lower levels of worthwhile than older adults.

Source: What matters for our sense of purpose briefing from the What Works Centre for Wellbeing

Drivers of purpose: what the evidence says

Our analysis finds that it’s what we do, and our associated health and ability to do it, that matters when it comes to our sense of purpose. This is different to our overall life satisfaction which is more influenced by the conditions around us and what we have. However, how we feel about our health is the biggest driver of our sense of purpose and our life satisfaction, which is similar to the health sector measure of healthy life expectancy.

Having a job that is meaningful is clearly important for our sense of purpose, but so is what we do outside of work; leisure satisfaction is also associated with a sense of purpose. Further evidence findings of that we can do to support our sense of worthwhile are:

- Spending leisure time outdoors.

- Carrying out moderate to vigorous physical activity, at least weekly.

- Engagement in cultural activities and membership of organisations.

- Social prescribed activities.

Our wealth was less important for our feeling of purpose compared to our overall satisfaction with life, but purpose was particularly low for those renting from social landlords. Compared to other measures of wellbeing like life satisfaction, our sense of purpose is more strongly connected to:

- Belonging to a religion,

- living with others in the house and

- having non-adult children at home.

Being in a job is a very big driver of overall wellbeing and purpose, although this analysis also highlights, perhaps intuitively, that having a high sense of purpose comes from:

- Looking after the home

- Working from home (for women).

- Volunteering.

- Working in the public or civil society sector.

- Self-employment or working for smaller organisations.

Two final findings that give pause for thought:

- Whilst having a garden or green space around us is good for our life satisfaction, it is using or being in the green space or garden that matters for a sense of what we do is worthwhile.

- People with poorer mental health found volunteering during the pandemic helped them to cope better with it.

Understanding wellbeing as a way to improve lives

Our aim with measuring wellbeing is to better understand what it is that makes the biggest difference to people’s lives. I believe that the purpose of government, the public sector and civil society, i.e. all of us in our collective actions, is to improve lives and life together. This data, and methods that can use it to inform decision-making in our collective life, can help us build lives, communities, systems and nations that ‘wire in what matters’ with what we value at the heart of it.

About the Author

Nancy Hey is the Executive Director of the What Works Centre for Wellbeing the UK’s national body for Wellbeing Evidence, Policy & Practice. The Centre aims to accelerate and democratise wellbeing evidence and practice focusing on what organisations – public sector, businesses, civil society – can do to improve wellbeing in the UK and to reduce wellbeing inequalities.

Nancy is a global leader in the field of wellbeing and has a wide range of advisory roles across sectors and around the world. Before setting up the Centre, she worked in the UK Civil Service in nine departments as a policy professional and coach delivering across UK Government policies including on constitutional reform. Nancy is a Fellow of the Institute of Coaching, A Harvard Medical School Affiliate, a Fellow of the Zinc Academy and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. She has degrees in Law and in Coaching & Development, specialising in emotions, and is a passionate advocate for learning systems.